It takes courage to experiment with any art genre when there is no guarantee of success. With such an-cient forms as Chinese calligraphy and various hieroglyphs any new interpretation is certain to draw acerbic criticism from purists, if not scorn. But this has not put off the well established, multi-award winning Chinese-American paint-er, calligrapher, and teacher Po Lau (Liu Qiufu/刘秋甫) who has, for more than five decades, wrestled with the whims of experiment to make something visually fresh with poligraphy and modern hiero-glyphic art. To Po Lau poligraphy is more calligraphy than painting: lively writing, some might say. But at its heart Lau's art is a dynamic cross-cultural journey embrac-ing language, philosophy, and the visual narrative power and immediacy of writing.

"My art does have a hybrid look because there are strong influences from both Chinese and Western culture and art," says Po Lau. "At the same time, I try hard to create my own identity and language of expression. This is how my hybrid look came about. Some people have suggested that my poligraphy is a new culture, not just an art form. [But] without knowing the culture, the lan-guages, and the visual forms, philosophy and having life experiences of both the East and the West, I could not have cre-ated poligraphy and my all-directional perspective flying landscapes."

The terms poligraphy and re-verse poligraphy are new and surprising to people. So what is poligraphy? "It is a new English calligraphic art style, using the Latin alphabet. Yet at first glance itlooks very much like Chinese calligra-phy," says Po Lau. "The forms are not made by just by stacking the original alphabets together: in most cases, there is hardly a trace of the English letters in the writing. Each word could be written in so many different ways and forms. By following the rules and guidelines found in A Dictionary of Poligraphy, one can create one's own reasonable and readable poligraphic alphabets, words and styles. Even hieroglyphs can be created.

"Poligraphy is combined term for pseudo calligraphy. A poligraphic word can be formed in different ways in block structures. They can be boxy (like Chinese characters) or cursive. They are written with the alphabet moving from the top to bottom and left to the right, similar to the way that Chinese charac-

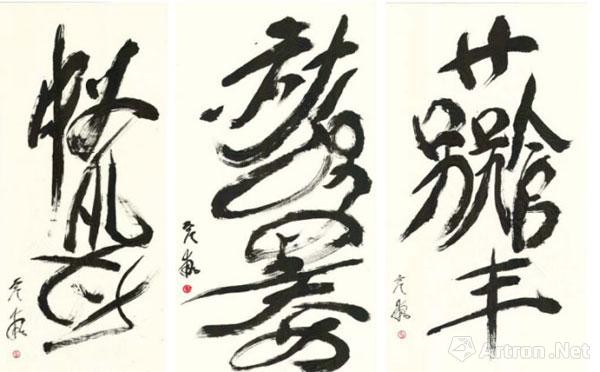

Po Lau, (from left) Loyalty, Integrity, and Honorable, poligraphy, 35 x 19 inches each. All images: Courtesy of the Artist.

Po Lau, Modern Mona Lisa, 2013, poligraphy and hieroglyph, 40 x 6 inches.

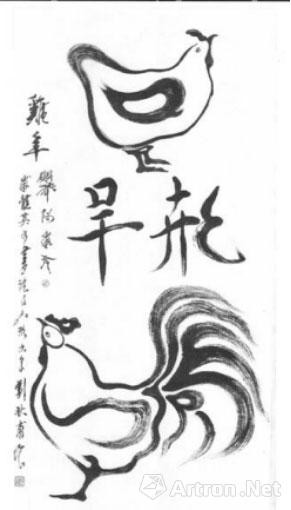

Po Lau, Year of the Rooster.

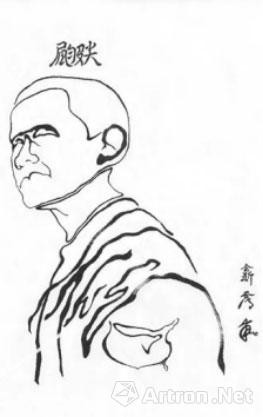

Po Lau, President Obama, 2013, poligraphy and hieroglyph, 45 x 35 inches.

ters are written. Reversed poligraphy is developed from the same concept and system of poligraphy, created by forming the Latin alphabet into new Chinese-like characters. New Chinese hieroglyphs can be created by applying the same rules."

Born in Hong Kong, on October 14, 1940, Po Lau graduat-ed from King's College and Northcote (Teacher)

Training College. Here he studiedImpressionism with an Italian artist. Later, he studied Chinese painting and gradu-ated from the Liching (Chinese painting) Art Institute, and went into teaching until 1969, when he went to the United States to the University of Southern California from which he received his MFA degree in 1971. Privately, Lau studied Egyptian art and some naïve art forms so that later on he "would not feel [that I was] being arrogant and that I was completed by dif-ferent cultures and arts. I felt that I needed to go somewhere like America to broaden my vision and improve my fundamentals as an artist. Looking back, I believe I have done both."

With his varied artistic and cultur-al training Po Lau was marked as some-one who would be willing to take risks. This is clear in his poligraphic and hiero-glyphic creations. But what inspired him to make art that bridged the East and the West? It was the most quotidian aspect of both: writing.

"As a student of art, I felt that English calligraphic forms lacked the powerful physical and artistic appeal like that of Chinese calligraphy," says Po Lau. "I always want to do whatever I can to bring the East and the West closer for the better understanding of each other. Peace brings a better life. As a student of art and calligraphy I found that Chinese and languages with the Latin alphabets have many similarities. I believed I could con-vert the English system—and other lan-guages—into a dynamic, pure artistic form like that of Chinese calligraphy.

But working with various forms of written languages to make artworks, or as one may say in Po Lau's case, writ-ing paintings, one does not work alone entirely in shaping the results. Po Lau's influences and experiences are broad indeed, Eastern and Western, ancient and modern, writing and painting, draw-ing and caricature, as well as landscape art. Among the ancients, Lau points to Jin dynasty (265–420 AD) government official and writer Wang Xizhi (303–361 AD), who, says Po Lau, was the greatest Chinese calligrapher, Yuan dynasty artist Wang Meng (1308–1385), Huang Binhong (1865–1955), Thomas Moran (1837–1926), and Paul Cezanne (1839–1906), as well as many other 20th century artists. The artistic and intellectual achievements of these artists inform much of Po Lau's art. One sees it in his boldly lined and subtly colored landscapes entitled

Landscape 2014–2 (2014) and Landscape 2016–7 (2016). These works speak both to Chinese traditions and Western mo-dernity as well as a robust line that ad-dresses the vitality of nature. There is something intensely personal about these landscapes, something that suggests a longing to grow, reaching for the vitality of growth. "I have constantly struggled to develop my artistic personality. At the same time, I do not want to lose my artis-tic Chinese connection. I have observed that my landscapes are now a combina-tion of a Chinese literati mood and both impressionist and expressionist colors."

Creating one's own contempo-rary hieroglyphs is an interest-ing challenge. Po Lau has met the challenge with both the seriousness of the professional and with a humorist's light touch. Works such as Modern Mona Lisa (2013), George W. Bush (2013), President Obama (2013), and others, as well as Slim Horse (2017) and Year of the Rooster (2017) speak to Po Lau's qualities. These qualities are informed by life and social experience that in turn highlight the versatility of his innovation in English (poligraphy) and new Chinese (reverse) poligraphy/ hiero-glyphs, a natural development from polig-raphy. "The presidents and famous char-acters are a small part of my choices. I chose some recognizable personalities to demonstrate how my

poligraphic system can create very realistic hieroglyphs."

Po Lau, Landscape 2014–2, 2014, ink and rice paper on revolvable board, 43 x 24 inches.

While many famous artists of other eras has informed Po Lau's aesthetic, his students have also played an important part in realizing his art. "When I was teaching school, I did not have students.

They were my friends; and still are. They were also like my teachers, literally. When they did something good, I learned from it. When they did something wrong, I also learned from it. Teaching is like a mirror. It reflects on what you do, what you can or can't do. It made me humble. And it makes me try harder and work harder."

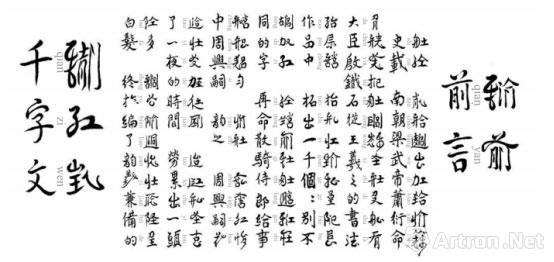

Making Chinese character-based and Western Latin alphabet-based cal-ligraphic forms to speak to the modern world, to unite distinct visual and literary cultures as well as one's own emotional and artistic identity is a subtle intellec-tual challenge that has defeated many fine artists. Lau's A Quote by Mark Twain (2013) and three cursive works Loyalty, Integrity, and Honorable (all 2016) as well as his ten-meter-long monumental calli-graphic scroll titled 1,000 Characters and the complex and lyrical I Have A Dream, (a 15 meter-long scroll of Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech) can be fully enjoyed as purely aesthetic experiences without the knowledge of either calligraphy or hiero-glyphs. Persuading people to appreciate the new and the fresh here is Po Lau's "immediate challenge" but it is his "per-sonal conviction. It is a huge challenge."

The differences in writing systems are among the most striking aspects of civilizations. They are more often than not underappreciated as they are seen as mere commonplaces in culture, yet they are fundamental to all our communica-tions, from the simplest personal state-ment to the most complicated diplomatic communiqué. For Po Lau poligraphy "is pure calligraphy. Painting may have all the elements of art or just one or two."

Yet however one may define callig-raphy and painting, writing and drawing, they demand the attention and respect for that which they are and can be. Po Lau understands the expressive nature of each. As he says, "Calligraphy is like a domestic horse. It runs under certain restrictions. Painting is a wild horse, which has the freedom to run any way it wants."

Po Lau loves fantasy and is a dreamer of unusual dreams, as one sees in his art. He is also an artist who aspires to encourage people to look at their realities in different ways, seek-ing new visual experiences that will help them to grow as questioning individuals.

If one knows both Chinese and English, Po Lau's art is easier to under-stand, but it can be difficult at times, one has to work at it. Yet, Po Lau is certain that his art helps people to understand Chinese culture and to learn something about it. This is something that makes Po Lau proud and more than willing to con-tinue to experiment.

Po Lau, 3-D sculptural Chinese Landscape, ink and color on rice paper and mixed media, app. 171 cm high.

By Ian Findlay

Copyright Reserved 2000-2024 雅昌艺术网 版权所有

增值电信业务经营许可证(粤)B2-20030053广播电视制作经营许可证(粤)字第717号企业法人营业执照

京公网安备 11011302000792号粤ICP备17056390号-4信息网络传播视听节目许可证1909402号互联网域名注册证书中国互联网举报中心

京公网安备 11011302000792号粤ICP备17056390号-4信息网络传播视听节目许可证1909402号互联网域名注册证书中国互联网举报中心

网络文化经营许可证粤网文[2018]3670-1221号网络出版服务许可证(总)网出证(粤)字第021号出版物经营许可证可信网站验证服务证书2012040503023850号